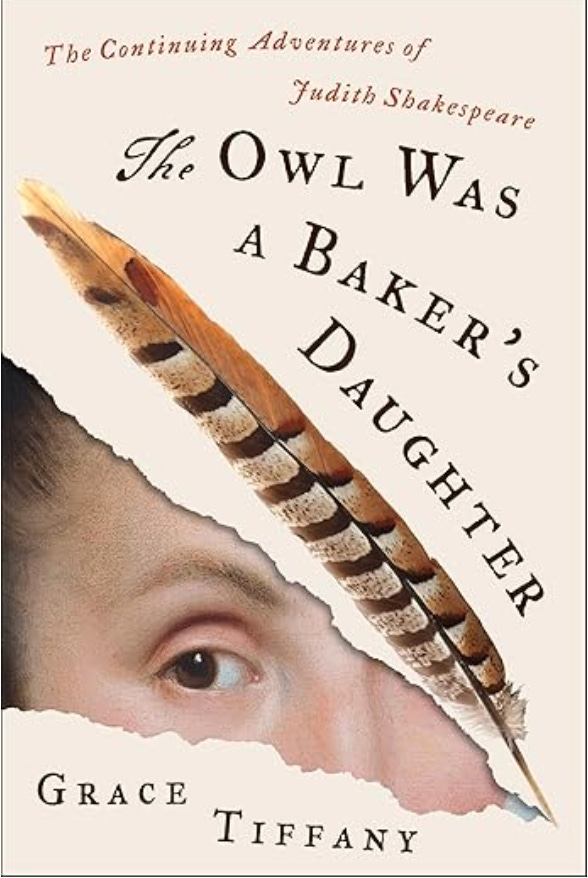

Taking Flight: A Conversation with Novelist & Shakespearean Scholar Grace Tiffany, Author of The Owl Was a Baker's Daughter

The continuing adventures of Judith Shakespeare, the Bard's younger daughter

Literary journal submission alert: Mid-American Review is open for prose, poetry, book review, and translation submissions. Guidelines and link to submit are here.

A list of writer and artist residencies in the U.S. and abroad can be found here.

Fiction writers: This fall I’m teaching a 10-week online introductory novel workshop for Stanford Continuing Studies. Class begins Monday, 9/22. More information and registration portal here.

Bookish yearly and monthly subscriptions are currently 30% off.

—

Greetings fellow scribes and literary travelers,

Today’s post is an interview with writer and Shakespearean scholar Grace Tiffany. Her new novel, The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter, is one I read with uncomplicated joy—its wisdom, humor, and suspense made me feel alive in the singular way the best books do. Set in 17th century England, the narrative follows Judith Shakespeare, William Shakespeare’s younger daughter and twin of Hamnet (who died in a drowning accident at age 11), now a 61-year-old midwife-apothecary.

Fleeing accusations of witchcraft and leaving behind a faltering marriage, Judith embarks on a perilous journey from Stratford to London (and beyond) with Jane, a young Puritan woman, and Jane’s niece, Pearl, this pair displaced by civil war. Harrowing incidents and adventures abound, but Tiffany is often wryly funny, and her characters are as vivid as anyone you might meet outside your front door.

And now—Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears.*

Christine Sneed/Bookish: What drew you back to Judith Shakespeare, one of William Shakespeare's two daughters, in The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter, who is also the protagonist of one of your prior novels, My Father Had a Daughter? I’m wondering as well how your perception of Judith evolved as you wrote about her as a woman more than 30 years older than she is in My Father Had a Daughter?

Grace Tiffany: For a long time I’d toyed with the idea of writing a sequel to My Father Had a Daughter, mainly because I knew that the real Judith Shakespeare had so many years yet to live, and would live through such interesting times. She died at the age of 77 – one of William Shakespeare’s last direct descendants – having experienced the reigns not only of Elizabeth I, James I, and Charles I, but the English Civil War, the public execution of the king, and the Interregnum, or rule of Parliament, followed by the first two years of the monarchy’s Restoration.

My last novel ended with the death of Shakespeare in 1616, but she lived until 1662, in a country which endured huge cultural and political changes, including the closing of the theaters under the puritanical Parliament, and their reopening under that madcap Charles II. And very little is known about her life during that time, so there was a canvas for imagining how Judith might have participated in all those changes; how things would have been for her personally.

CS: Judith is a midwife-apothecary in The Owl Was a Baker's Daughter, a socially precarious role in seventeenth century England, which is riven by civil war between the Royalists and the "Roundheads," Oliver Cromwell's supporters. I'm guessing this was her actual profession. What kind of research did you do to bring Judith and her work so vividly to life?

GT: Ah, but here you’d be wrong, because, as I say, little is known about the life of the real Judith. Her history’s a “blank,” like Viola’s in Twelfth Night. It is known that her sister Susanna Shakespeare’s husband, John Hall, was a well-known physician who lived in Stratford. So, to give my character something interesting to do, I made her his assistant – this was back in the first novel – and then his successor in The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter. Unusual, but credible.

I researched medical (or quasi-medical) practices of the period, books of herbalism and natural cures, including the somewhat weird Paracelsian practices of Doctor Hall, which involved ingesting minerals. A lot of it was probably not all that healthful, but what did they know? There was wisdom mixed with nonsense.

I also read about battlefield surgical practices, because Judith becomes a kind of field surgeon, and, of course, the symptoms and attempted cures for the plague, which was always a threat in the seventeenth century. Lots of authors have researched these things more deeply. I’m quite sure Geraldine Brooks, author of Year of Wonders (set in the plague year 1666), did much deeper research.

I wanted enough lore to provide texture and give Judith’s imagined occupations credibility for the reader. But I was most interested in other aspects of the plot – getting her out of Stratford, letting her meet up with an old actor friend, getting her involved in some political intrigue.

CS: The novel opens with Judith fleeing from Stratford after she's accused of witchcraft. What inspired you to explore the ways women’s knowledge and independence were both valued and feared in her time?

GT: What you’ll read, and it’s largely true, is that in the seventeenth century, officially qualified male doctors, especially in urban areas, were wanting to arrogate the baby-birthing trade to themselves, and this made it difficult for traditional midwives to earn a living. I don’t think this was true as much in the country, or country towns like Stratford, where Judith practices.

However, when she comes to London, she encounters various legal barriers to her practice. So she goes underground. As for the witchcraft charge, it’s also true that charges of witchcraft, mostly aimed at women and often at herbalist healer types, ramped up in the seventeenth century, as what seems to have been a kind of pre-Enlightenment last gasp of religious superstition. (In America, even the devout Puritans of Salem lived to repent their crazy witch-hunt and admit it was nuts.)

I don’t think there was any correspondence between the witch-fears and the attempts of urban doctors to safeguard their profession from female practitioners; I think these things were independent phenomena, but some scholars would probably disagree with me.

As for my interest in the topic of women’s feared independence: I don’t think many characters in the book, male or female, fear “independent” women. (The quotation marks are there because people weren’t really “independent” in the sense we mean, and didn’t regard themselves as such; they had masters, wives, husbands, children, relatives; few people sustained themselves alone.)

When Judith’s accused of witchcraft, it’s a woman who accuses her, and it’s men who defend her, and in fact, that whole episode is a small part of the plot. Judith doesn’t experience many limits on her freedom because of her sex, largely because she doesn’t seek or imagine some kind of total independence. Nor does her far more radical companion, Jane, though Jane goes a bit farther out there, to say the least. But what these women do is within the bounds of historical possibility.

I hope I’ve avoided writing the kind of book where a modern woman, with a modern female mindset, strangely occupies the body of a seventeenth-century wife. She would have thought differently than we do about her available roles as a woman.

CS: The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter’s exploration of war, politics, and religious zealotry also feels strikingly relevant to the present era. What parallels do you see between Judith's and our own?

GT: It was very different. Most people were religious, and the war, which was religious as well as political, was waged between two sectors of society who had very different ideas about how to practice the Christian faith. It’s tempting for people to identify the Puritan reformers with contemporary Christian nationalists, but the comparison doesn’t hold.

The zealous puritans of the seventeenth-century were not conservatives. They were the progressives. They wanted to divest the king of his authoritarian power and to increase the power of elected representatives, the House of Commons, and of local assemblies. The Royalists, on the other hand, were worshipful of the king, largely aristocratic, highly ritualistic, and not generally representative of the popular will. King Charles himself thought he ruled by divine right.

In that respect, he’s like Trump, except Charles was intelligent, and actually a king, and Trump’s just a brash and ignorant golem who strangely ended up in the White House. The Royalists of the seventeenth century actually had a tradition of kingship to fight for, whereas those who welcome Trump’s attempts at absolute rule seem not even to know their own country’s constitution and history. And England had a legislature that stood up to the autocrat. Four hundred years later, we don’t have that. Not anymore.

CS: You’re a Shakespearean scholar and have taught for many years at Western Michigan University, and before WMU, at other universities. Were you already writing fiction when you were studying for your Ph.D. at Notre Dame? and writing your dissertation?

GT: Back in my 20s I wrote some bad science fiction short stories, but in graduate school I got sidetracked into writing the essays and articles you write in a graduate English program. I shouldn’t say “sidetracked,” because I really enjoyed writing literary analysis, and I still write journal articles about Shakespeare and others. I didn’t start seriously writing fiction until well into my academic career, and in fact it was my research into the history and culture of the Elizabethan theater that inspired me to write a story about playwrights of that time.

CS: What are you working on now?

GT: I am trying to refine and improve a translation I made of the late Mexican novelist María Luisa Puga’s first book, Las posibilidades del odio. But I’m also beginning a third and final novel in the “Judith” series, only the main character in this one isn’t Judith, but her adopted granddaughter, the character Pearl in The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter. The new book is set in 1665, and Pearl is a Restoration actress, struggling to keep the old Shakespearean traditions alive in a world of outrageously silly manners comedies, and to evade all the Restoration Harvey Weinstein types that control acting opportunities. But at least women finally get onto the stage.

An excerpt from The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter:

Grace Tiffany is a professor of Shakespeare and Renaissance literature at Western Michigan University, and the author of seven novels set during the early modern period. Her first work of fiction, My Father Had a Daughter, was recognized as an outstanding novel of 2003 by the Association of Independent Booksellers. Her current novel, The Owl Was a Baker’s Daughter, is a sequel to the first. Tiffany has also written articles and monographs about Shakespeare and his literary and dramatic contemporaries, and has translated works by the Argentine author Jorge Luís Borges and the Mexican author María Luisa Puga.

📗 🍩

* From Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar

Sounds like a wonderful read! Thanks for showcasing it, Christine.