Sex, Death, and Love: A Conversation with Writer and Chicago Quarterly Review Editor Syed Afzal Haider

Syed's new book is The Dying Sun and Other Stories

If you’re in the U.S. and celebrated Thanksgiving yesterday, I hope you had a convivial meal. My partner Adam and I are in the Palm Desert for a few days and had a quiet meal last night prepared in the little kitchen of the place where we’re staying. The hummingbird in the photo below often drops by the patio and perches at the top of a small oleander bush.

Before today’s feature, a couple of items of note:

2025 Plentitudes Prizes in Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry & Flash: Four grand prizes of $1,000 each and publication in The Plentitudes is given annually for a single poem, a work of flash fiction or nonfiction, a short story, and an essay. Using only the online submission system, submit up to three poems of no more than 65 lines each, a work of flash fiction or nonfiction of up to 1,000 words, or a story or essay of 1,000 to 5,000 words with a $20 entry fee. The submission deadline is December 31, 2024, at 11:59 PM ET.

May 18-24, 2025, I’m leading a writing retreat in Bordeaux, France hosted by Foreword Retreats. All genres and levels of experience are welcome. Lodging is in a chateau north of the city, with meals prepared by an on-site chef. Registration deadline is Jan. 10, 2025. Please apply soon—space is limited.

Bookish subscriptions are 30% off through the end of the year. A preview of November’s agent list can be found here. December’s agent list will be published next Thursday.

—

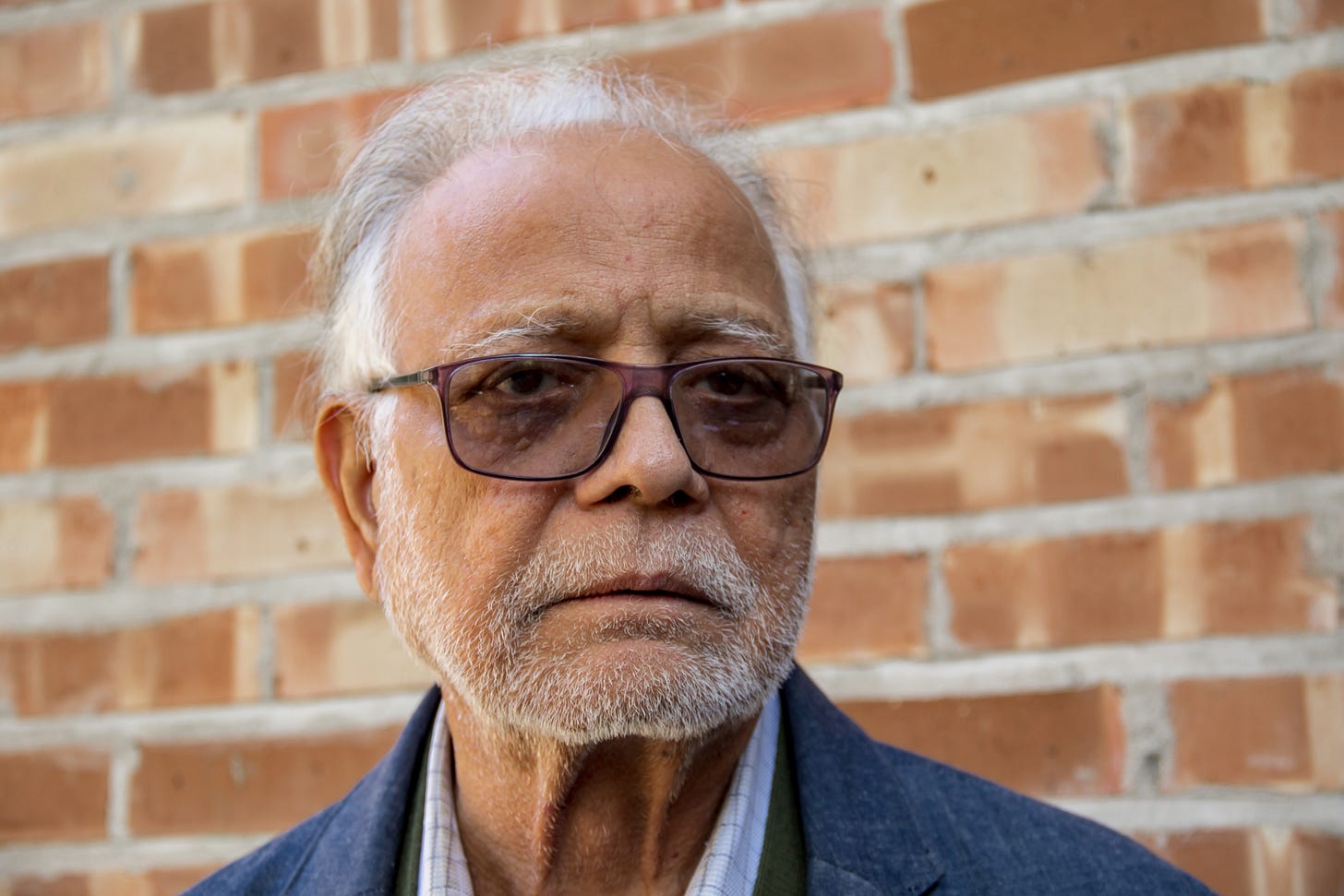

Recently, I had the pleasure of peppering writer and editor Syed Afzal Haider with questions about his third book/first story collection, The Dying Sun and Other Stories, published last month by Weavers Press. Syed has resided in Evanston, Illinois for many years, where he writes fiction, co-edits Chicago Quarterly Review, and is a steadfast and generous champion of many writers.

Christine/Bookish: You’ve published two novels, To Be with Her and Life of Ganesh, and now a short story collection, The Dying Sun and Other Stories. You’ve been writing fiction for a long time, while also working as an engineer and later, as a social worker. How did you begin writing fiction?

Syed Afzal Haider: After working 10+ years as an electrical engineer, I came to realize it wasn’t my cup of tea. I then dropped out and studied psychology, enrolling in a program to become a clinical psychologist—I guess mostly to figure out and find myself. During that period, my 57-year-old mother got sick with a fast-growing cancer in Karachi, Pakistan, and soon after, I traveled there from my home in the U.S.

The seventh day after her surgery (which removed a cancerous tumor), my mother passed away, as they say, peacefully surrounded by her family, and loved ones, after wishing her five daughters and two sons a good life, asking them to be kind and caring of their father. Upon returning to the U.S., in the vertigo of loss, I was in no mood to become a clinical psychologist.

I dropped out the clinical psychology program and got an MSW instead and began working as a social worker at a school for delinquent boys, dealing with sociological difficulties in human situations, using psychological methods and systems. And then I experienced a major loss, the sudden death of the love of my life, my first wife, mother of our infant son.

I worked fifteen years as a social worker at the school for boys, a single father at home, grieving the death in our family. By 1989, I had collected my share of injuries, harms and damages…I had accumulated my share of losses and made a major decision to escape to writing and become a practicing writer.

“I don’t think of myself as giving up work to be a writer. I’m giving up work to, at last, be,” John Fowles once said. I had been keeping a journal most of my life. I was writing social and family histories, treatment plans, interviews and summaries.

This was the time in my life when in my mind I was a writer. But that does not make one a writer. I lacked the tools, I needed to learn how to write and be a writer, and that is when I joined Molly Ramanujan’s fiction writing classes (in the Graham School of the University of Chicago).

Someone asked poet Donald Hall, “What do you write about anyway?”

“Love, death, and New Hampshire,” Hall replied.

I believe in true love and I truly believe in death. And love’s death I know I can’t forget, hence dying for love is worth writing about and worth dying for.

CS: I believe you told me that there are some autobiographical elements in your new collection The Dying Sun and Other Stories. Would you talk about the experience of melding fact and fiction in these stories? How do you ensure that the terms of the story aren’t upended by what actually happened?

SAH: Good writing and the writer’s voice help make sense of the story. I think all fiction is memoir, as all memories are fiction. Not line by line, or word for word. I develop more or less the same feelings about my characters as I’m telling my reader, and your love losses show in everything you say and do. The shadows of death that show on your face, the life you knew that ended on that day your love passed away.

Of love, loss, lust and longing and dislike, the hardest for me to write is hate. [The story] “The Other Man” was difficult to write. I don’t know how it came about, but I also know exactly how it did.

The title story, “The Dying Sun,” is about a friend who visits from Berkeley, who is now a retired doctor and still lives in the Bay Area. And Marty is/was an old clinical psychologist friend, Mark, who I recently lost. Adam is my son, who lost his mother when he was an infant. The motherless child was obsessed with astronomy. One of his favorite books was My First Book About Space, A question and Answer Book, By Dinah L. Moche, Ph.D. Illustrated By R.Z. Whitlock.

Regarding sexual scenarios, as a young man I devoted plenty of time and energy reading the oldest Hindu textbook of erotic love and sexual positions, the Kamasutra, without a partner. Kama/desire/love//pleasure/sex, Kama is also the name of Hindu god of erotic love. Sutra/a treatise.

By the way, Wendy Doniger and Sudhir Kakar’s English translation of Kamasutra from Sanskrit is a pretty good read.

But writing sex is not easy, the sex acts may be real but the characters are fiction, or the partner may be based on someone real but the acts are imagined. It’s all a part of the writer’s fantasy.

I think all fiction is memoir, as all memories are fiction.

CS: The stories in The Dying Sun are set in India, Pakistan, and the U.S., places you know well. You also write about childhood, parenting, and dating after becoming a widower. What led you to the decision to write short stories, rather than a novel or memoir or essay collection?

SAH: …in the beginning, when the world was believed to be flat, I was writing short stories, and was having minor success in getting published. Then, my good friend and agent—(I don’t think she’d mind if I share this)— the poor woman sent my short story, “Brooklyn to Karachi Via Amsterdam,” to a famous editor at The Atlantic, who seemed to like it, and made some valuable comments, but rejected it. So I re-worked the story a bit based on his remarks. Then instead of sending it to my agent, I sent it directly to the same famous editor at The Atlantic… he rejected it again…admonishing me: “Syed, I have rejected this story already.”

I thought, Maybe I shall try hand writing a novel!

I gave thirty or so published stories to my publisher to be published as collection. They curated and published only thirteen of them, saying nobody will buy a thick collection of short stories by an unknown writer. Maybe one day they will publish Volume II, in which Doris gets her oats.

CS: You’re a co-editor of Chicago Quarterly Review, which has published many poets and prose writers since its founding 30 years ago. Would you talk a little about how an issue comes together?

SAH: Back in the spring of 1994, CQR was born out of conversations among a few friends. We shared a belief that the work of many good and talented writers was not reaching a readership through conventional venues.

In the early days of the CQR, we published the work of writers and editors of our acquaintance whose work in some way matched our vision and personal preferences. When we celebrated our 25th anniversary in 2019, we invited our staff to contribute in the tradition of the olden days, and recently for our our 30th, we did so again.

We are small, but in time have carved out a niche in the independent literary world. We have been honored to have the work of our contributors appear in Best American Short Stories, Best American Essays, The Pushcart Prize Anthology, and The O. Henry Prize Stories. Our special issues have been reviewed and used in university courses, including our Chicago issue, Italian Literature issue, South Asian American issue, Australian issue, and our Anthology of Black American Literature. A special issue on Native American writing, guest edited by Brandon Hobson, is now in the works.

The heart and soul of CQR is our all-volunteer staff, and we are still blessed with a growing group of friends who grant us their time, energy, and enthusiasm.

I’m blessed with likes of John Blades, Gary Houston, Jake Young, Signe Ratcliff, Umberto Tosi, Chuck Kramer, Christina Drill, all seasoned writers, poets, and editors. The crown jewel is my friend and fellow senior editor Elizabeth McKenzie. Lisa works twice, maybe three times harder, and takes care of four times more work. She is the engine that carries CQR from beginning, from selection to production, from page one to the end. That is how each issue comes together—teamwork. We read, write, and talk writing.

Our true joy, the “labor of love: or “love of labor,” comes when we can showcase the writing of young and new as well as seasoned and established writers.

We now have many hundreds of submissions to choose from.

CS: What are you working on now if you don’t mind sharing a few words about it?

SAH: This brings us back to the beginning. My first novel, Incomplete Conversations/Before Cartoons, needed more work. Strangely enough, I’m working on a very long novel, sent back again by my agent who said, “It needs an ending.” So I’m writing the life of the same characters fifteen years later in their lives.

It certainly is a very good writing exercise, a trick-and-treat moment…There are no rules and no formulas. Incidentally, accidentally I started reading Kaveh Akbar’s first novel Martyr. Akbar is a great poet…this being his first novel, he showed me a way to go out of sequence in the life of my characters, so for now I have a good mentor in Akbar. I probably will need a good editor in the near future.

I just upgraded to a paid subscription so that I could point out that I caught the "In which Doris gets her oats" allusion made by Syed Afzal Haider. He's echoing the words spoken by John Lennon in the introduction to the song "Two of us" on the Beatles 'Let it Be' album.

Per wikipedia:

+++++

At the beginning of the recording Lennon says,

"'I Dig a Pygmy', by Charles Hawtrey and the Deaf Aids... Phase One, in which Doris gets her oats!"

The joke was mixed in by Phil Spector for the Let It Be album and also appeared in the Let It Be film, both released in 1970. "I Dig a Pygmy" is an obvious reference to Lennon's song "Dig a Pony" that follows in the album's track order. "The deaf aids" – a British term for hearing aids at the time – was also the nickname given to the Beatles' Vox amplifiers.

+++

The 'in which Doris gets her oats!' line has a pretty intense personal meaning for me as well, for reasons we shan't go into right now.