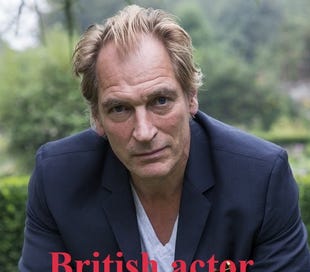

I live about an hour from Mt. Baldy, a popular hiking spot that’s also the location of the Rinzai Zen monastery where Leonard Cohen spent time in 1996 traveling his soul’s byzantine corridors. More recently, Mt. Baldy has been in the news because it’s where the British actor Julian Sands disappeared this past January. Despite dozens of searchers—both amateur and professional—combing the area in the last six months, no traces of him have been found.

Mt. Baldy, the highest peak in Los Angeles County (elevation 10,068 feet), is several miles north of the east-west 210 freeway, up a steep, well-traveled road. Sands was (is?—although it’s unlikely he staged his disappearance—more probable is that because snow and ice still cover parts of the peak, some areas remain unsearchable; there’s also the darker possibility his remains were carried off by wild creatures) an experienced hiker, but the weather in Mt. Baldy and environs from November through April was intermittently stormy and very rainy. Hikers, no matter how experienced, were advised to avoid the perilously muddy trails.

Tangentially, mudslides along the California coast are increasingly common due to climate change and ongoing human encroachment into terrain previously left undisturbed. In 2017, Big Sur was inaccessible for months other than by helicopter due to a mudslide that destroyed a bridge and buried long stretches of the Pacific Coast Highway. This year, once again, the highway was closed because of massive mudslides brought on by one blustery downpour after another.

Sands doubtless knew the risks, as did at least one or two other hikers who likewise disappeared or were found dead on Mt. Baldy this past winter, but couldn’t keep himself from returning to the mountain despite the dangers it posed.

Long ago, right in the middle of the Reagan years—to which, at 14, I was all but oblivious, my mother took me to see A Room with a View at a movie theater in Middleton, Wisconsin, a town a few miles outside of Madison. I was a high school freshman visiting her over spring break; she was in her first year of veterinary school at the University of Wisconsin. For weekends, she’d drive home to northern Illinois where, when the school year wasn’t in session, she lived with my father and me.

I remember the movie theater as an odd, cavernous structure, its walls made of corrugated metal, none of this of any consequence once A Room with a View began. From the first scene in a Florentine pensione, it felt as if I really had been spirited into the enchanted foreign territory of this film, which is both a love story and a lightly comic examination of English classism set in Italy and Edwardian England. I hadn’t seen anything like it before, and I didn’t know at the time it was based on an E.M. Forster novel, which I read a few years later in college.

This 1985 Merchant-Ivory production was perfectly cast: Helena Bonham-Carter as its young heroine Lucy Honeychurch, Daniel Day-Lewis as her patronizing suitor Cecil Vyse, Maggie Smith as Lucy’s much-older cousin and travel companion Charlotte Bartlett, Rupert Graves as Lucy’s adorably goofy younger brother Freddy, Simon Callow as the Reverend Mr. Beebe, Julian Sands as romantic hero George Emerson, and Denholm Elliott as kindly, plainspoken Mr. Emerson, George’s father.

One of the film’s most memorable scenes takes place on a hillside in Fiesole, a village outside of Florence. Puccini’s “Chi il sogno di Doretta,” sung by Kiri Te Kanawa, provides the soundtrack as Lucy makes her way unsteadily toward George who rises up from where he sits fanning himself with his hat and takes her into his arms. When Charlotte spoils the fun a moment later, Lucy is flustered and deeply smitten, George’s avid, impenitent gaze on her as she is whisked back to Florence with a few other members of the group of well-heeled English tourists (among them the novelist Eleanor Lavish played by Judi Dench, who memorializes the kiss in a passage Cecil, by then Lucy’s fiancé, unknowingly reads aloud to her and George many months later), she and Charlotte traveled to Fiesole with earlier that day.

To my uncynical teenage heart, Julian Sands as George Emerson appeared the ideal suitor—burnished, poetic, impetuous. Sands’ George reminded me of someone I’d had a crush on for nearly two years by that point. (Several years later, the first time I saw The Way We Were, Robert Redford also reminded me of this classmate—the crush unrequited, but it smoldered on for years, as I suppose adolescent crushes often do.)

Reading the news this past January that Sands had disappeared in the mountains outside of Los Angeles, a city where he’d lived for years with his second wife and their children, brought on a strong bout of melancholy and nostalgia, as well as the irrational thought, How could I not have known he lived so close?

In the scene leading up to the hillside embrace, off-camera, George can be heard shouting, “Truth! Beauty! Love!” while the others in his group picnic among the wildflowers. Unruffled, Mr. Emerson explains to his bewildered companions, “George is proclaiming his creed.”

It feels both cruel and entirely apropos that Sands disappeared into the wild. I imagine he spent some (all?) of his career trying to escape the long shadow George Emerson cast over the roles that followed (there were other good ones, however, including those in Mike Figgis’s Leaving Las Vegas and Timecode).

Nearly forty years have passed since A Room with a View’s release. Like a song or a scent, a beautiful film is a time machine, a vehicle fueled by nostalgia. I don’t know if Julian Sands will ever be found, but we do have his performance, arch and joyful, in this sublime film.

I think I need to (re)watch that movie this weekend!

Well done!