On Thrillers, Mysteries, and Rock Stars: A Conversation with Novelist, Music Critic, and Memoirist Sarah Tomlinson

Sarah discusses her debut novel, the rock-world thriller The Last Days of the Midnight Rambler

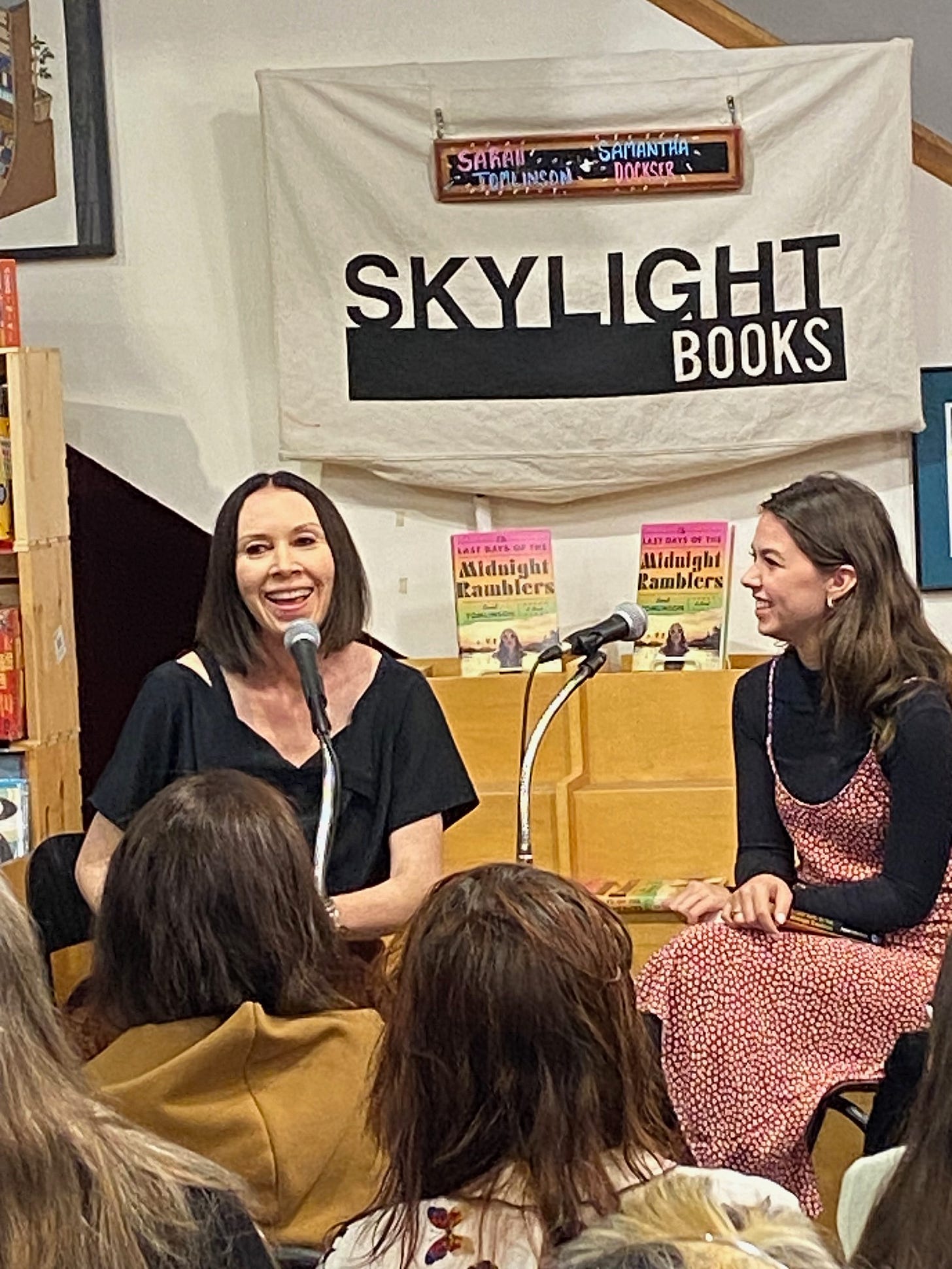

I met

(whose excellent, music-focused Substack is ) last May in Los Angeles at a book event for a mutual friend. It was an unseasonably cool night, but spirits were high—our friend’s book was doing well, and it was almost summer. After the reading, Sarah and I had a long, discursive conversation about film, TV shows, and books.During our chat, I learned that after working as a music critic in Boston, Sarah had moved to Southern California in the mid-aughts and transitioned to ghostwriting. She has published more than twenty books as a ghostwriter, and has also written a memoir, Good Girl (2015), under her own name. Her first novel, The Last Days of the Midnight Ramblers, was published by Flatiron Books in February.

Good Girl is supple and effortlessly engrossing; I had a feeling that her novel, when I got my hands on it, would be just as immersive, and I wasn’t disappointed. Set mostly in 2019, The Last Days of the Midnight Ramblers is told from the point of view of ghostwriter Mari Hawthorn, who inadvertently becomes involved in a decades-old mystery surrounding the death of Mal Walker, the founder of the rock band the Midnight Ramblers.

Mari has been commissioned by Mal’s widow, Anke, to write her memoir. Anke is a legendary model and style icon and was a witness to the fraught relationships among band members and staff who were with Mal on the night he died—she is also a person of interest in his death. Before long, Mari’s own life is in peril—some in the Ramblers’ inner circle have no desire for Mari to expose their dark pasts.

(Our interview was originally published in ZYZZYVA - the full text can be accessed here.)

A mystery is a “who done it,” and a thriller is a “why done it.”

Christine/Bookish: Before you became a novelist and ghostwriter, you were a music critic for The Boston Globe and other publications. Have you been carrying the idea for The Last Days of the Midnight Ramblers since the era when you were reviewing concerts and albums and crossing paths with rock stars such as Bono and Cat Power?

Sarah Tomlinson: I stumbled into music journalism in my mid-twenties after trying my hand at food writing (which I loved, but my editor confessed she worried about my recipes, and rightly so, as the stove in my apartment only had three working burners). I found I had a great passion for music, and it was a wonderful way for me to work on the craft of writing and on developing my critical skills. I’ve never been or wanted to be a musician, so I wasn’t precious about music in the same way I sometimes have been when considering my own writing or work by other writers.

I loved my musical community—my friends and lovers, who played in some of my favorite bands; my friends who worked as publicists, A&R scouts, club promoters, and roadies. We were a family who took care of each other (as much as we were able to, given that we were mostly young works-in-progress, and there was a lot of drinking—that’s rock and roll, baby!). I earned the nickname Duchess of Rock and did my best to live up to it.

I’ve always wanted to write a novel set in the rock world. My first novel, Because the Night (still in a drawer), was very loosely inspired by the life of Lucinda Williams, who became a friend after I confessed this to her at a record label Christmas party. The book detailed the complicated romantic relationship of two musicians who played in the same mid-level alternative rock band and the aftermath for the female singer after the male guitarist died.

I also wrote a TV pilot, All Access, about a young female music journalist with bad boundaries (sound like anyone we know?). But, originally, the idea for Ramblers was given to me by my longtime agent and friend, Kirby Kim, while we were having drinks in New York in 2016. He said, “You should write a thriller about a ghostwriter.” At the time, I didn’t really take in the idea, as I wasn’t a big reader of thrillers. But Kirby is smart and knows me well. (Plus, he knows all of the crazy stories from my life as a ghostwriter, most of which we can never, ever, tell publicly.)

So, the idea kicked around in the back of my mind until I sat down to give it a go in 2018. One of the first questions I had to answer, of course, was what kind of memoir my ghostwriter Mari would be hired to write. I had heard some music industry gossip following the publication of one of the big rock memoirs about a scandal that had been left out of the book. Whether or not the rumor was true, it made me think this was the perfect, ripe territory for my ghost to inhabit.

I purposely made the characters older—contemporaries of the Rolling Stones—because I had particularly admired their role in pop culture history and the originality and daring of their most famous paramours: Marianne Faithfull, Anita Pallenberg, and Uschi Obermaier, who informed one of my main characters, Anke.

Also, I thought it was important that, although they became famous during the tabloid age, they had much more privacy than celebrities today. And they received more respect and deference as creators, which I felt gave them more agency to teach Mari something about being an artist and living well, beyond lessons in navigating fame.

I’m fascinated by celebrity and have spent quite a bit of my adult life around famous people, whom I’ve learned a great deal from, but I’m not sure how interesting “fame” itself is—as many famous people have attested, it can be a terrible trap.

Of course, once I started writing the scenes involving the band, I realized I was penning a big love letter to rock and roll and my time in that world, which informed me as a woman and writer.

CS: This novel’s chapters begin with epigrams that, taken together, could be the basis of an instruction manual for ghostwriting. Were these instructions in the book from the beginning, or did this structural choice come after you’d already been writing for a while?

ST: Again, Kirby gets credit for this idea. He maintained that one of the central reasons for writing this book was that readers love to learn about a whole new world. And so, I should set out to teach them everything I could about being a ghostwriter.

The working title was How to Be a Ghost. The book is written in a three-act structure, and originally, each act opened with a page-long lesson about ghosting. But this setup wasn’t quite working. My lovely editor Zack Wagman at Flatiron, who is brilliant at pacing and structure, helped me see that having a short lesson at the start of each chapter was the better choice.

By this point, each chapter had already been titled for a concept that would be helpful to a ghostwriter (“Seduce,” “Intuit,” “Leverage”), which corresponded to the challenge Mari was facing in those pages. And so, I simply made sure each lesson was applicable to that particular chapter. This was some of my favorite writing because it helped me hone in on what being a ghostwriter means to me; for example, it was while doing this type of prescriptive writing for the book that I realized I’ve felt unconditional love for all of my clients. This was important for helping me understand Mari and why she risks as much as she does for her clients in the novel.

CS: This novel strikes me as part mystery, part coming-of-age story, part family saga. Was the mystery at the center of The Last Days of the Midnight Ramblers the galvanizing narrative force from your earliest draft?

ST: It’s been explained to me by crime writer friends who are much more knowledgeable on the subject that a mystery is a “who done it” and a thriller is a “why done it.” My book is definitely a “who done it.” I knew Mari needed to solve a mystery during her ghostwriting assignment.

The rock world is full of real-life “mysteries.” So many accidental deaths and suicides have been rumored to be murders, including the drowning death of Brian Jones, which very loosely influenced my book.

I think because we have such deep love for our musical idols, and feel their passings so deeply, we almost can’t handle the idea that it was just a stupid accident or a symptom of how much psychic pain they were in/how bad their drug use really was.

I had always thought I might like to write a nonfiction investigation of one of these mysteries, but I’ve never gotten around to finding one that had the legs to sustain a whole book. Also, getting to make up the elements of the crime and the potential suspects was way more fun, and ultimately satisfying, because my motivations for the “crime” were character-driven, and my characters are always, for me, the most interesting part of every book I write.

I’m so glad you saw it as a family saga and a coming-of-age-story, which is one of my favorite genres (especially when it’s adults who come of age, which I feel is true for so many of us). As I maintained in my memoir Good Girl, and as Mari says, having a complicated relationship with a parent who has struggled with addiction or mental health issues is the perfect petri dish for breeding a good ghostwriter. So, I knew Mari’s family was going to play a part in her own coming-of-age story.

CS: There are four female characters in The Last Days of the Midnight Ramblers. Mari, of course, along with her younger sister Vivienne, legendary beauty Anke, who was romantically linked to three members of the Midnight Ramblers, and her friend Sigrid, who is the band’s manager/fixer. These women all drive the story as much, if not more so, than the focal male characters—Dante, Ody, Jack, and the long-dead Mal. You upend the groupie stereotype with these four women—can you comment on their characterization?

ST: Although Mari and Anke are the main characters, all four women are equally important to the plot and each other’s character development.

One thing that’s interesting about being a ghostwriter and being around celebrities is that you often receive very candid feedback about your appearance, bearing, and performance. I think this is because most celebrities, especially entertainers, are openly judged on these merits, and so they do it to others without thinking.

And let’s just say it’s hard to feel like a beauty around some of the most gorgeous (and well-maintained) figures in our popular culture.

Also, in my experience, women are often grouped and group themselves into either being pretty or smart. And, for better or worse, they end up cultivating their natural assets accordingly. So, I wanted to write two characters who were known for, and in some ways supported themselves, with their beauty (Anke and Vivienne) and two female characters who were known for, and in some ways survived by, their wits (Sigrid and Mari).

But the only way this would be interesting was if the women had surprising things to teach themselves and each other about what it means to be beautiful and what it means to be smart. So, I forced myself to dig deeper in my writing of these characters to make sure they weren’t just stereotypes.

I always knew Mari was based on me, particularly in the period of my career when I was trying to land my first project as a ghostwriter. It wasn’t until I had finished writing the book that I realized Anke was also, in a way, based on me. In my twenties and thirties, I had several lovers who were (moderately) famous musicians. As I wrote in my memoir, I didn’t have the self-confidence or emotional maturity to handle those relationships very well at the time.

And yet, they were important mentors who helped me learn how to be a working artist and think of myself as one. I do believe I was a part of the music those men were making in those years, and the support system that helped them to keep touring even though they were both dealing with substance abuse issues back then. So, I wanted to write another version of the story where I showed how important the women who are intimate with creative men can be.

I think Cameron Crowe captures some of this in Almost Famous. Touring is incredibly lonely and destabilizing. The men who do it often date a lot of women, which could make it seem like the relationships aren’t ever deep. But these men often need the women around them in a way that is hard for people on the outside to understand.

When I wrote my memoir, only one of my old lovers asked to read the material about him and let me use his real name. This meant so much to me, not just because he verified my story, but because he cared enough about me to do this. I had a lot of feelings about changing the other men’s names at the time. Because they were at least moderately famous, I felt like I needed to respect their wishes and privacy. But I also felt like my own story and perspective had value that wasn’t being acknowledged.

As I’ve gotten older (and I hope, wiser), I’ve gained a much greater understanding of what was at risk for them; they lived from their music, had public personas they’d created, sometimes had girlfriends, and in the two cases I’ve mentioned, drug problems during the time of our involvement. And although we had passionate affairs on and off for a decade, did I really know and understand the full landscape of their lives well enough to tell their stories for them?

By now, I have much more sympathy for everyone’s position. As Ramblers alludes to, but I didn’t entirely understand when I wrote my memoir, it’s a tremendous amount of responsibility to be the person telling a shared story. It should always be approached with as much generosity, compassion, and humor as possible. And so, although Anke is not me, I put a great deal of my own experience into her character and made sure she was respectful of the men she’d loved and did not, in fact, tell all about them; she instead preserved everyone’s dignity.

**

Sarah is available for book club discussions and for speaking engagements on a multitude of writing-related subjects. Please drop a note to Kirby Kim, kkim@janklow.com, if you’re interested in inviting Sarah to talk with your group.

**

Creator bio: Sarah Tomlinson is a Los Angeles-based writer. She has more than 15 years of experience as a journalist, music critic, writer, ghostwriter, and editor. She has ghostwritten or co-written fourteen books, including the New York Times bestseller, Fast Girl, with Suzy Favor Hamilton, and two uncredited New York Times-bestsellers. Her father-daughter memoir, Good Girl, was published by Gallery Books (Simon & Schuster) in April 2015.

After growing up in Maine, Sarah attended the early college, Bard College at Simon’s Rock, and then earned a BA in Creative Writing at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. After four years spent writing and buying records in Portland, Oregon, she earned an MA in Journalism at Northeastern University in Boston. While in Boston, she launched her journalism career.

Sarah currently writes novels, memoirs, screenplays, TV pilots, personal essays, short stories and online dating profiles for her friends.

Fascinating stuff! She's had quite a journey, from critic to ghost to novelist and memoirist and TV writer. Each one requires different skill sets, but she knows how to build off each genre strength and adapt them to other forms. Thanks for this. I learned a lot.

Great interview. I love who-dun-its and look forward to reading this one.