On Tennis, the Art of Biography, and SoCal v. NorCal: A Conversation with Writer and Tennis Journalist Joel Drucker

And how tennis was transformed from an acoustic lawn party into an electric carnival

Today’s post is an interview with fellow writer and Southern California resident Joel Drucker. After Joel read my second book, Little Known Facts, he sent me a kind note, and a few years later, we met in person when I was in his (now-erstwhile) neighborhood for an event at Book Passage in Corte Madera, CA with Peter Orner (also an erstwhile NorCal resident—Peter’s new book was Am I Alone Here? Notes on Living to Read and Reading to Live. I was there to promote my second story collection, The Virginity of Famous Men).

A number of years earlier, Joel had published his first book, Jimmy Connors Saved My Life: A Personal Biography, an excellent biography of the fiery tennis star as well as a recounting of Joel’s own formative years as a tennis player and his path to becoming a writer. His second book, published in 2017, Don’t Bet on It, is a propulsive, beautifully written memoir about his years with his wife Joan who died of lupus in 2010.

Over the last decade, Joel and I have had many conversations about books (along with films and tennis luminaries—Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic perhaps especially). He’s one of the most committed readers I know, and it’s always good to hear his take on the books he’s reading and to commiserate over the writing life.

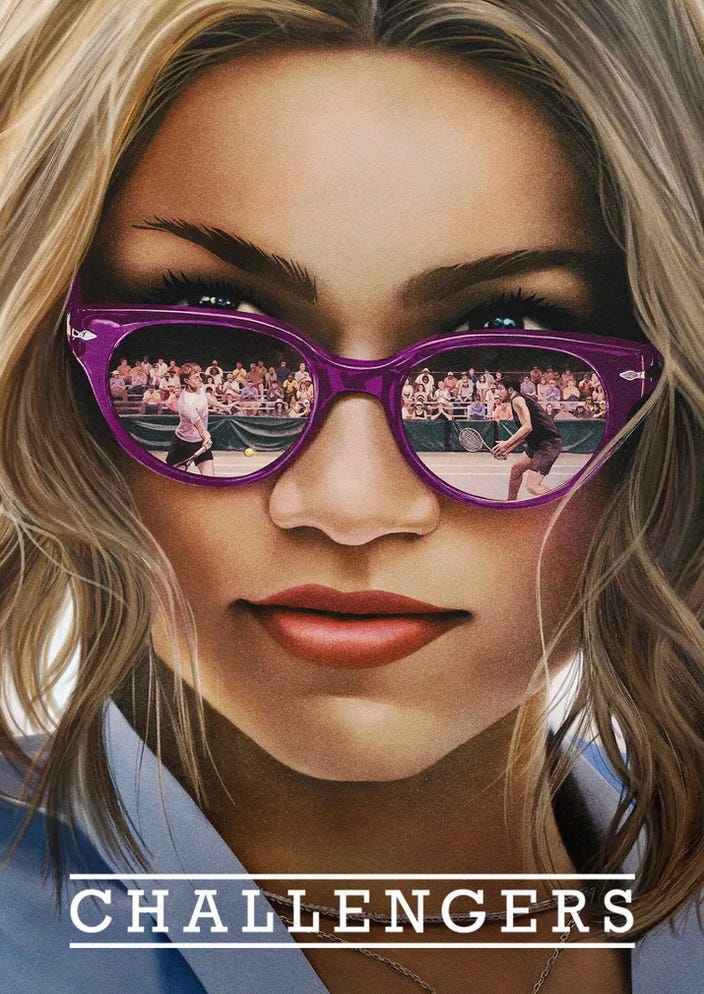

Lastly, Joel recently reviewed Luca Guadagnino’s new film Challengers for tennis.com - you can find that review here.

Christine/Bookish: As mentioned above, you're a serious reader, probably as well read as any other writer I know. How did you get interested in books? I'm guessing it was from having books in your home, i.e. a parent who read avidly?

Joel Drucker: Both of my parents were constant readers. Our bookshelves included a lot of the books I ended up reading in college – zeitgeist-capturing sociology works like Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd, novelists Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Norman Mailer, and John Dos Passos, and historians such as William Manchester, Theodore White, and Arthur Schlesinger.

There were also lots of entertainment industry books floating around our home, be it the memoirs of a studio mogul to numerous Hollywood biographies. We also had plenty of humor collections from people like S.J. Perelman, Dorothy Parker, and James Thurber. I didn’t read all these books, but in retrospect, I see that simply being around them greatly fueled my comfort with ideas and authors.

So while my parents weren’t scholars – my dad worked in the jewelry business – they put a big premium on reading not just as something you did in school, but as part of your personal operating system. When I was a teenager, I once told my mom how frustrated I was with a certain friend’s intelligence. “What can you say?” she asked. “He’s not a reader.”

CS: Your day job is tennis journalist, but you've also published creative nonfiction in periodicals such as Tin House and Los Angeles Magazine. You've likewise published two books, Jimmy Connors Saved My Life, which I'd describe as a sports biography and memoir hybrid, and Don't Bet on It (which Billie Jean King blurbed: “Joel’s story of Joan is a beautiful and passionate tale of two first-rate competitors who fought hard for their love.”) How did you get into tennis journalism?

JD: I majored in history at UC Berkeley, soon enough with the desire to be a writer. In a place like that, where ideas were constantly in play with great classes and thoughtful professors, my quest was to write about politics and culture, akin to such role models of mine as George Orwell, Joan Didion, and James Baldwin.

The plan once I graduated in 1982 was to be part of a program called “Cal in the Capitol,” wherein I’d go to Washington, D.C. All was lined up for a unpaid internship at a publication called Roll Call for which I’d cover Congress. Or better yet, learn to cover Congress, as much of my prior journalistic experience had been working not on the college newspaper, The Daily Cal, but its humor magazine, The Pelican.

But all those years I’d also been a tennis zealot. I’d played since I was 12, competing all over tennis-rich Southern California. And while I wasn’t good enough to play college tennis at Berkeley (the team was No. 2 in the country when I was a sophomore), during summers I taught and continued to follow the sport.

So in the spring of ’82, less than two months before graduation, I had the chance to write for a local tennis magazine. Soon I got a job offer – one that actually paid. And I came to see that in certain ways, tennis and I were meant for one another. It was like the movie, It’s A Wonderful Life. For all Jimmy Stewart’s desire to travel the world, he comes to see that the real love of his life is the girl next door, played by Donna Reed. Tennis was my Donna Reed – and indeed, at the tennis magazine, I ended up meeting Joan, whom I was with for 28 years.

I thought I was put on earth to tell the world the story of Jimmy Connors and how he'd transformed tennis from an acoustic lawn party into an electric carnival.

CS: Jimmy Connors is a famously polarizing figure in the tennis world. I'm so curious about how you came to write Jimmy Connors Saved My Life.

JD: Though I’d initially hated this roguish tennis player, by the time I was 16, I’d come to adore Connors. Nearly six years later, I was in a writing class and attempted to mimic Joan Didion and write a piece about my family and tennis titled, “When the Music’s Over.” The instructor said that while he couldn’t quite understand what I was saying about my family, he thought there was something rich in the tennis and that I ought to try writing more about it. That even preceded the work I did for the local tennis magazine.

So for the next piece, I thought I’d write about my favorite tennis player. I stole the structure from The Great Gatsby – Connors as the Gatsby-like man of action, me as the Carraway-like man of thought. The piece was written in May 1982. As fate had it, Connors by this point had gone nearly four years without winning a major title. But in July, two weeks after my graduation, he won Wimbledon.

And thanks to a good friend of mine named Dave Engelberg, Connors had the chance to read the piece soon after. Also thanks to Dave, I was then able to meet Connors and get an interview with him. Fancy that – barely a month after graduating, I was able to interview the Wimbledon champion. Think of it like a tennis version of Cameron Crowe’s movie, Almost Famous.

At that point, in the wake of having studied history and knowing so much about tennis and Connors, I thought I was put on earth to tell the world the story of Jimmy Connors and how he'd transformed tennis from an acoustic lawn party into an electric carnival.

Over the next 20 years – no joke – writing that book remained a North Star of sorts for me. I wrote numerous pieces about Connors, was once even asked by him to write a proposal to be his ghostwriter, a request that triggered a 65-page document.

During that time, a novel Joan and I were reading provided great imagery for what I hoped to accomplish. We were both reading Anne Rice’s first three Interview with the Vampire books. The first one took place near us, in San Francisco. It’s easy to forget that the person who starts off the tale is a journalist, keen to get the same thing I wanted from the legendary, enduring Connors: to hear the life story of a blood-thirsty killer who’d mastered the art of longevity.

Then Joan turned this on its head. “As a biographer, you’re a vampire too,” she said. “You sink your teeth into your subject’s neck, you suck out all the blood, and then you think you’re going to live forever.” Well, well – and so vivid and true. I soaked it up right way.

Along with that, I came to better understand the true emotional pull of Connors for me, digging into some deeply personal, family matters, particularly around a tragic series of events that happened to my older brother, Ken. So while I didn’t get to be Connors’ court-appointed Boswell, I ended up writing a book-length version of that original essay. Amazingly, six years after it was published, Joan died – on Connors’ birthday, September 2. More recently, Ken died on September 3, 2021.

CS: After many years in the Bay Area, you moved to L.A. a couple of years ago. How has this relocation affected your work in tennis and your writing in general?

JD: After living in L.A. from ages 10 to 18, I went north for college and stayed there for more than 40 years until I was 61 years old. So at heart, my adult life was built in Northern California – from UC Berkeley, to love and marriage, to working in downtown San Francisco for ten years, buying property and more.

But the years after Joan’s death were frequently painful. And so, around the time I helped my LA-based mother relocate to assisted living, I began to ponder the idea of reinvention in a place both new and familiar. I vividly recall a breakfast I had with you, Christine, around that time. I was rereading John Updike’s Couples, and then you and I discussed what it was like to be a writer in L.A.

Operation Relocation has been fantastic. On the work front, it’s greatly helped me with the tennis writing. Like many parts of the country, Northern California has a zealous recreational tennis community, as well as elements of world class activity that occasionally lend themselves to work-related opportunities. For many years, that included two professional tournaments. Those events are now gone.

But when it comes to tennis, being in Southern California is akin to being a country music person and living in Nashville: a gold mine. For decades, with very few indoor courts, Southern California’s weather advantage helped it build the most vibrant tennis community in the world. Everything tennis-related just takes place here on a higher perch, so I’ve been able to find more people, places, and other story elements for everything from certain pieces to speaking gigs and a wide range of opportunities.

In the last month, for example, I’ve interviewed several active pros who are in town, attended a match at UCLA, covered two tennis-related film premieres and conducted research at one of the most iconic clubs in tennis history – all this within a 30-minute drive of my house. That couldn’t happen anywhere else in the world.

CS: You and I are both big fans of John Updike. Who else are the writers you read and reread?

JD: Often when I’m about to start a piece, I’ll reread the authors I’ve sought to stylistically emulate, be it Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, Didion’s White Album or any number of pieces by Orwell. For Tin House, I wrote an essay about Haywire, a memoir by Brooke Hayward, the daughter of an actress and an agent-producer, that I read three times at age 18, 28, and 50.

Recently I also bought Freedom by Maggie Nelson, an essayist I’ve enjoyed. And I just finished reading A Chance Meeting by Rachel Cohen, a series of 36 essays on various American cultural figures who encounter one another from the 1850’s to the 1960’s – from photographer Mathew Brady meeting Henry James to Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston to Norman Mailer and Robert Lowell.

No question, I’m drawn most to somewhat quirky non-fiction that’s a mix of personal and researched.

When it comes to fiction, a novel I really liked was Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, about a football player in the post-9/11 period. A couple of years ago, I took the plunge and reread Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom. It was a tough go, but eventually, worth the effort. And of course, I greatly enjoy the works of Christine Sneed, most recently reading Direct Sunlight.

Then there’s what I call comfort reading: easily digestible books that can be read when I’m tired, stressed, sick, traveling. For me, the topic here is popular culture and sports from the ‘60s and ‘70s. Favored reads include Sam Wasson’s The Big Goodbye, about the making of one of my favorite movies, Chinatown, and tennis legend Arthur Ashe’s year-in-the-life diary, Portrait in Motion.

**

An excerpt from Booklist’s review of Jimmy Connors Saved My Life: Jimmy Connors is seldom considered when one discusses the best tennis players ever. Nevertheless, he was the most successful, with an all-time best 109 tournament victories through the 1970s and 1980s…The chip on his shoulder that carried him out of Belleville, Illinois, and to a number-one world ranking…antagonized the press, his opponents, and the tennis establishment. But it was Connors' determination that inspired Drucker to pursue his career, hence the book's title. Readers will get twice what they expect here: this is not one story but two, and both make compelling reading.

**

Another wonderful interview, Christine. As a tennis bystander, I’m always looking for a way into the sport. Thanks to this compelling interview with Joel Drucker, I’m inspired to enter as a reader! Also fun to learn about others’ reading lists and influences that are as eclectic as mine.