An Improv Game Played Alone: Robin Romm on Her Newest Book, Radical Empathy: Stories

"What if a flower started harassing someone during quarantine?"

Hat tip to for this info: Headlands Center for the Arts (Sausalito, CA) is accepting residency applications through June 2. You can find out more here. Residencies range from four to ten weeks.

Next week I’ll be sending out June’s agent list. A preview of May’s is available here.

—

Earlier this spring I took part in a short story discussion panel at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, which is held on USC’s campus, usually in late April. One of the writers featured in the panel is today’s interviewee, Robin Romm.

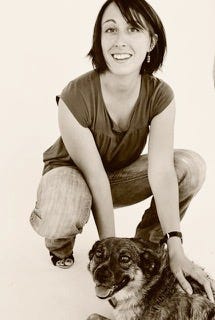

Robin is the author of four books—two fiction, two nonfiction: the story collections Radical Empathy and The Mother Garden, and the nonfiction books The Mercy Papers: A Memoir of Three Weeks and Double Bind: Women on Ambition.

At the Festival of Books, Robin spoke about her most recent collection, Radical Empathy. She has a great sense of humor and writes with what George Saunders calls a “line-by-line energy.” Many of her stories are funny and sexy, regardless of the weightiness of her themes (more on this below). I hope you’ll pick up a copy of Radical Empathy soon, and please consider asking your local library to order a copy too.

—

Christine/Bookish: What’s your process for developing a short story—do you start with a character, a scene, or a feeling?

Robin Romm: Short story writing, for me, is like an improv game that I play alone. I throw myself an interesting starting prompt and then I see what I can do with it, relying on the things I don’t know about my imagination to carry me through it. The more I think about an idea for fiction, the less it interests me when I sit down to write it. Stephen King wrote that you can’t expect to surprise a reader if you don’t surprise yourself first, and I believe this wholeheartedly.

Sometimes I start stories with a premise: what would happen if a woman bought another woman’s extra sperm and then became entangled with her family? Sometimes I start with an image: what if a flower started harassing someone in quarantine? Sometimes I just write lists of things I have observed or overheard until my imagination clicks into gear and then I cut those early pages and go where the wind blows.

CS: The stories in Radical Empathy explore, among other topics, parent-child relationships, marriage and domesticity, desire, and loss. How do you approach writing about these complex topics without tipping into sentimentality?

RR: I just spent twenty minutes wondering why these subjects would lead to sentimentality more than, like, dragons seducing mer-elves and have come up with nothing. Family and desire and sex—what could be more full of specificity, absurdity, and emotional complexity?

I think a writer’s fear of sentimentality consists of two parts: A) The fear of writing cliché (and being seen as lazy and probably dumb) and B) The fear of vulnerability.

I think a writer should fear cliché but be brave in the face of vulnerability. Risk sentiment in your work—or what’s the point? But do it bravely. And specifically. Be original and observant.

I can say all of this, but I suppose if I told a freshman writing seminar to write a mother who’d just had a baby, we’d get a lot of beautiful Madonnas in morning light. It’s still a little subversive (but fun, very fun!) to strip away our assumptions of women, particularly mothers, and see them as people. If I give myself this prompt, I immediately think of the days after I gave birth to Annie, my second daughter (who emerged so fast I had no time for drugs and on such a sea of amniotic fluid the doctor actually shouted “HOLY SHIT!” then ducked out of the way while holding her hands out to catch the baby).

I had to stay extra nights in the hospital for observation, and [my husband] Don and I couldn’t figure out what to name the baby. We held the baby and cooed over her. I nursed her and changed her. But I spent quite a lot of time during Annie’s first 48 hours trying to sweet talk various nurses into finding out what everyone on the floor had named their babies. This gave the hospital stay a little intrigue, the brief smack of detective work waking us all up from the stupor-inducing fans and lights. Ava, Cyprus, Harper, the nurses reported back. But the best one was a skater couple who’d named their baby girl “Ollie” after the jump. Hahaha.

Maybe we should name the baby after things we liked. Em Dash! Juxtaposition! Dim Sum! At the end of day three, the nurses told us that we had to get serious and find a name or we’d have to come back in, file paperwork, and pay an administrative fee to rename the baby. The idea of paperwork so horrified us that we stopped polling everyone. Don got into the hospital bed with me and we bandied about options, finally settling on Annie, after Annie Oakley, legendary sharpshooter, for reasons I will get to in my next book.

CS: You have what I'd call a light comic touch, which is apparent in many of your stories, even those where you're exploring grief and loss. Who are some of your primary influences?

RR: I absolutely love a smart, funny book, but they’re relatively rare. Lorrie Moore and Philip Roth are heroes of mine—both specialize in sharply observed absurdity tempered by strong feeling. Patrimony may be my favorite memoir of all time. I love Alina Bronsky—dark humor, dry wit.

Dave Eggers can also be funny for all the same reasons. I also loved the screwball humor of Sarah Levine’s Treasure Island!!!, Marcy Dermansky’s Hurricane Girl, Worry by Alexandra Tanner, Shmutz by Felicia Berliner. For a little humor calisthenics, I read David Sedaris. He writes so much that you can compare his truly funny writing with his sort of funny writing and get a master class in comedy.

I’m probably more influenced, though, by my father, who is very funny in a droll, understated, observant way. He was also very distracted when I was growing up, but I could get his attention with a witty observation or a nimble joke. That’s the real master class.

CS: How does your experience writing both fiction and memoir influence your short story writing? Do you find one form informing the other?

RR: I wanted to be a poet, but when I went to college, you had to apply to the poetry workshops. It was the 1990s and experimental poetry reigned supreme. I was an eighteen-year-old who just loved the passion and music of language. I didn’t get in. But when I submitted my long prose poems to the fiction workshop, they read like experimental fiction. I got in! So, I started writing short stories and fell in love with them. Short stories have a lot in common with prose poetry. The great ones are meticulous with no room for navel-gazing or wrong turns.

I started writing nonfiction in my late twenties, while staying with my mother during the final weeks of her life. I’d been writing fiction for years, but when confronted with all the wild, urgent nonsense that happens at the end of a life, I could no longer access my imagination in the same way. I just needed to record what was happening around me, distancing myself from it in some crucial way, while also remaining in the thick of it.

At the time, I felt very conscious of using all the fiction-writing skills I’d collected over a decade: quick, precise characterization, dialogue, detail, scene and time, to move the nonfiction along. To make art rather than journal. It felt like writing fiction, except the story was actually happening to me. I just had to catch it, see it, shape it. Now, with small kids, I find myself in a happier version of the same predicament, and lately have been writing another memoir with the same approach. I love both genres. Or maybe I don’t believe in genres. Did you ask me that?

CS: Is there a story in Radical Empathy that you feel particularly connected to or was especially fun to write?

RR: I had a lot of fun writing “A Gun in the First Act” and “Marital Problems,” two of the funnier stories in the collection, because I wrote them both in the spirit of entertaining myself.

I applied for and interviewed for a lot of academic jobs in the early aughts, and at the time, they took place in hotel rooms at AWP. As in “Gun in the First Act,” I did once find myself sitting on a hotel bed surrounded by indifferent men. And the one man joining via Skype audio really did take an audible piss while I was talking.

It felt great to make that scenario the starting point for a comedy, to put a gunman in that hotel and let the men’s true natures play out. I wrote “Marital Problems” when I had babies and very little time to myself, when autonomy and sexiness felt like exotic birds in another land. I loved writing the voluptuous, younger neighbor and the main character’s angular envy. Her projections. And I enjoyed writing all that sex because few things are as absurd, and yet as revealing. At least if you’re brave enough to pay attention.

**

An excerpt from “Marital Problems,” Robin’s O. Henry Prize 2024-winning story (edited by Amor Towles):

—