Olives, Polyamory, Maternal Gorillas! A Conversation with Fiction Writer Garnett Kilberg Cohen

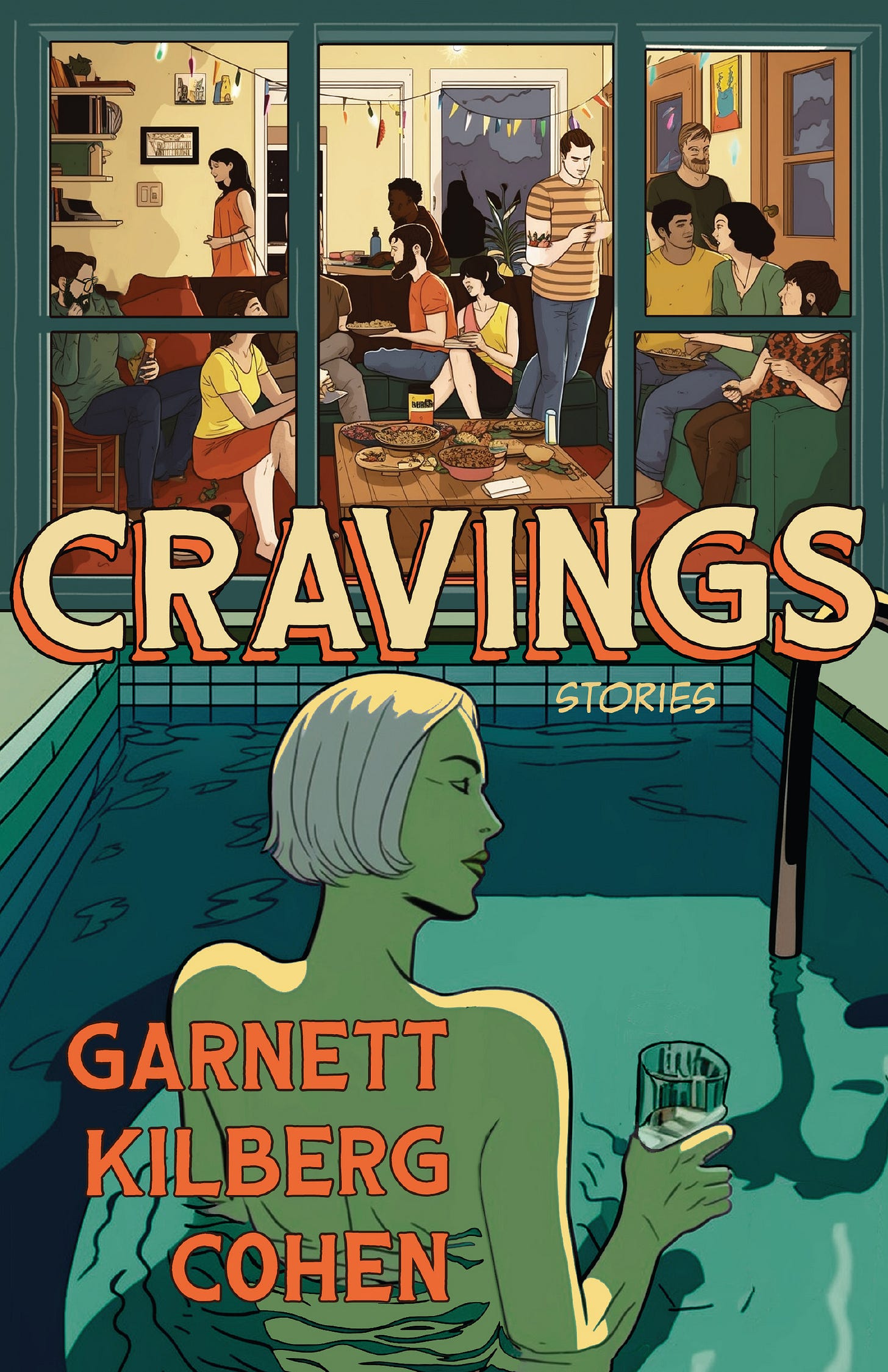

Garnett's new book, CRAVINGS: STORIES, is out on October 31

Before the interview with Garnett Kilberg Cohen, two items of note: submissions are open at South Dakota Review (poetry and prose, through April 30, 2024 - no submission fee), New England Review (nonfiction and dramatic writing only - through midnight ET, Nov. 1), and Iowa Review (nonfiction only - through midnight CT, Nov. 1). Get ‘er done if you have new work to submit!

This Sunday, October 29, 6 PM CT, I’ll be reading in an online Sunday Salon Chicago event with Jimin Han, whose new novel The Apology, was recently published, Alex Wells Shapiro, Taylor Byas, and A.S. Coomer, hosted by novelist Ignatius Aloysius. Free event but registration is required—Zoom link sign-up here.

Cravings is Garnett Kilberg Cohen’s fourth story collection, and these new stories are vividly imagined and assured in their craft. Each was such a pleasure to immerse myself in. I had the opportunity recently to ask Garnett a few questions about her new book, which is officially out on Halloween. 📗 🎃

The storied Chicago indie bookstore Women and Children First (5233 N. Clark Street), will host Garnett’s release party, Nov. 8, 7 PM. Garnett will be joined in conversation with her friend and much esteemed fellow fiction writer Rosellen Brown. Information about other events featuring Garnett can be accessed here.

Christine/Bookish: The stories in Cravings are impressively wide-ranging. In “Wheels,” for example, your main character is an elderly man whose car keys have been confiscated by his son and daughter. In “Feast,” a Michigan farm woman in her mid-40s befriends and subsequently betrays her new neighbor from New York City. In “Maternal Instinct,” a young man remembers a formative childhood experience with a gorilla at the zoo. Each story is its own fully imagined world. Do you usually begin with a subject or a character in mind, or perhaps the narrative voice?

Garnett Kilberg Cohen: My stories come from a variety of sources, sometimes an image, a memory or a snippet of an overheard conversation. The three stories you mention provide good examples of the different ways inspiration can work for me. “Wheels” came from two things—first watching my young grandson push his tiny cars through the dirt and wondering who he would be as a man, and from a conversation I had with my father about the fact that I thought my mother (not him) should stop driving. Once I had those two things, I was able to push forward and invent the rest. Maybe other small images and details from my life are there, but I’d have to re-read the story to see—certainly nothing significant.

The narrative voice drove “Feast.” I heard about a polyamorous couple and wondered how it would work to put this free-thinking couple in an environment where people would not be accepting of their lifestyle. I started with a formerly religious woman as their neighbor. I found her voice and POV and quickly got in her head. The story flowed naturally from there. Writing almost felt like following her around.

“Maternal Instinct” began when I heard a news piece about a boy falling in a gorilla pit (at least I think it was a gorilla pit) in the zoo. That’s all I knew, nothing else, not even the location of the zoo. I wondered what it would feel like to fall in a gorilla pit, how his parents felt, and how the experience would affect the rest of his life. My imagination took over from there.

CS: The POV character in “Ogden, Ohio,” is a woman who had a baby during her last year of high school and subsequently raised her daughter on her own. Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio is mentioned a few times in “Ogden”–I assume your story is an homage (you’re from Ohio, if memory serves?) Do you see yourself writing more about this town or perhaps you have already?

GKC: The epigraph, a quotation from Sherwood Anderson, at the beginning of the book is probably the biggest way I’m influenced by Anderson: “The true history of life is but a history of moments. It is only at rare moments that we live.” Like Anderson and Virginia Woolf, in Moments of Being, I believe that when we think back on the past, it is the moments of clarity, shame, grace and transformation that stand out and make up our lives, not the vast stretches of time that make up most of our everyday lives.

That said, I did love Winesburg,Ohio, and I am fascinated by small town life. I grew up in the village of Hudson, Ohio, which only had about 3,000 people at the time, a small village surrounded by farm land (I lived in the village). Doors were left unlocked (in fact I remember my mother once telling me she had no idea what had happened to the keys) and people knew the stories of their neighbors (often down to intimate details), even if they didn’t know them personally—though they usually did.

In many ways it was idyllic and the friendships made are ever-lasting, but life was also, paradoxically, both secretive and too public. I’ve written about small towns before and will again—though not necessarily the fictional Ogden. In real life, at this stage of my existence, I prefer the anonymity of a city most of the time, but nothing beats walking barefoot in the grass.

CS: Tangentially, how important is place to you in a story? The stories in Cravings all, to my mind, have vivid settings–whether it's a Chicago neighborhood or a rural Midwestern town or a small town in Montana.

GKC: It depends in part on the story. Many of the things that happen in small towns or the countryside could not happen in the same way in bigger cities. The last two stories in the book are very dependent on place, particularly the last one, “Feast.” The landscape—rural and isolating in some ways—helps create the inner life of the main character, Val, and the conflict in the story comes in part from the mindset of the local people. In my stories, I always want readers to be able to see the characters’ surroundings, the physical details, but sometimes, my stories are focused so much on the characters’ inner lives that the actual region where the story takes place isn’t quite as important.

CS: You’ve published 3 other story collections, Lost Women, Banished Souls; How We Move the Air; and Swarm to Glory. Of course I’m curious–have you written a novel or are you working on one now? Or will it only ever be short stories?

GKC: Yes and no. I have written a few novels that didn’t ultimately feel successful to me or to the places (agents mostly) I submitted them. There were a couple of “almost, but no cigars.” (I just looked up that expression and see its origins come from the fact that in the 1920’s carnival game owners often gave out cigars as prizes to adult winners.) I have not felt the compulsion to continue revising them. I did start a new novel well over a year ago, which I like a great deal, but I kept taking breaks to write stories or essays and then Cravings got accepted and, as you well know, a lot of time goes into preparing a manuscript for release and then promoting it. I am hoping to go back to it in the spring when I have a greater expanse of time.

CS: Like Alice Munro, Grace Paley, and Lorrie Moore, the short story is your primary mode. What is it that most attracts you to this form? Its brevity, its compression, its stricter narrative demands (compared to the novel)?

GKC: All of the above! As many have said before me, the story has some of the same elements of compression & precision of language found in poetry, yet focuses on characters and their plights and transformations like novels. It is people (even made-up ones) that intrigue me. I love to read novels but in most cases (far from all!), they seldom feel as artful to me. For pure aesthetic pleasure, I generally like to see the whole arc of a piece (whether that be a painting, a poem, a play, etc.) in one viewing or sitting.

Plus, in terms of my writing time (and the way my brain works), I like to switch up genres and subjects. When I’m done writing a story, I might think of an essay I’d like to pursue or an entirely different type of story. Though my writing is generally within traditional literary boundaries, I feel I can experiment in a story or an essay more than in a sustained piece.

Maybe the main reason is that a novel takes such a commitment of time that I feel I must put too many ideas on pause while working on one. I’m a little impatient. I’m hoping that might change now that I’m retired from academia. I loved teaching and felt very fortunate to have a full-time academic position, but it didn’t allow as much creative time as I would have liked. From the outside, teaching three days a week might not appear time-consuming, but in-class time doesn’t include the class preparation, the outside reading, the paper grading, the committee work, and writing letters of reference and promotion.

Garnett Kilberg Cohen’s three previous collections include Lost Women, Banished Souls; How We Move the Air; and Swarm to Glory. Her writing has appeared in The Antioch Review, TriQuarterly, The Rumpus, Witness, The New Yorker online, The Gettysburg Review, among other places. Her honors include four awards from the Illinois Artists Council, including a Fellowship for Prose, the Crazyhorse National Fiction Prize, the Lawrence Foundation Prize from Michigan Quarterly Review, and two Notable Essay citations in Best American Essays.

A professor at Columbia College Chicago for over 30 years and chairperson for eleven years, Garnett has also served in editorial positions at Another Chicago Magazine, South Loop Review, Punctuate: A Nonfiction Magazine, and Fifth Wednesday. You can learn more at her website http://garnettcohenauthor.com.

Happy weekend and take good care, fair readers and fellow scribes. I leave you with a photo from the Audubon Society:

Thanks for the post, Christine. Always inspiring.

Inspiring interview on the writer's process! Plus, the new work sounds like I have to read it! Happy Halloween!